St John Street Station opened in 1871 on the site of the former monastic hospital of St John. It was the northern terminus of the Midland Railway from Bedford and London St. Pancras. The Midland Railway was absorbed into the London Midland and Scottish Railway in 1923. On the 3 July 1939 the station was closed and trains diverted to Castle Station. The impressive sandy-coloured limestone building was converted into offices after closure but was finally demolished in 1960 for a car park.

I recently came across this piece written by my father, Arthur Ward, in 2012 but it tells of his exploits at St John’s and along the line in the 1930s.

St John’s Street Station

St John’s Street Station was the Midland Railway’s terminus in Northampton and the second station in importance of the three stations in the town coming after Castle and before Bridge Street Stations. It provided a connection with Wellingborough and Bedford both on the Midland main line to London St Pancras and to Leicester and Sheffield to the north.

A double track from Wellingborough joined a double track from Bedford in Midsummer Meadow near the Britannia Public House on the Bedford Road and then separated with one arm going along to Bridge Street level crossing and the adjacent Bridge Street Station, whilst the other rose on an earth embankment through Becket’s Park over Victoria Promenade into St John’s Street Station.

Forecourt and entrance to St John’s Station

St John’s Street Station was an imposing Midland Railway building which probably got most of its business from the buses that terminated there. It was built on a mound with a large forecourt which served as a terminus for a number of private operator country bus services that were fighting to survive the monopoly of United Counties Omnibus Company which scandalously ran a schedule at the same time as a local operator but at a loss making lower price in order to put them out of business.

One day at around 1.30pm I was passing the new Regent Square traffic lights on my way to Campbell Square School when a private operator bus possibly from Brixworth turned from Barrack Road into Campbell Street, in a flash two or three men ran out and slashed the bus tyres and quickly vanished into the lunch time crowds on their way back to the shoe factories. I doubt if they were ever caught even if the United Counties were held to blame.

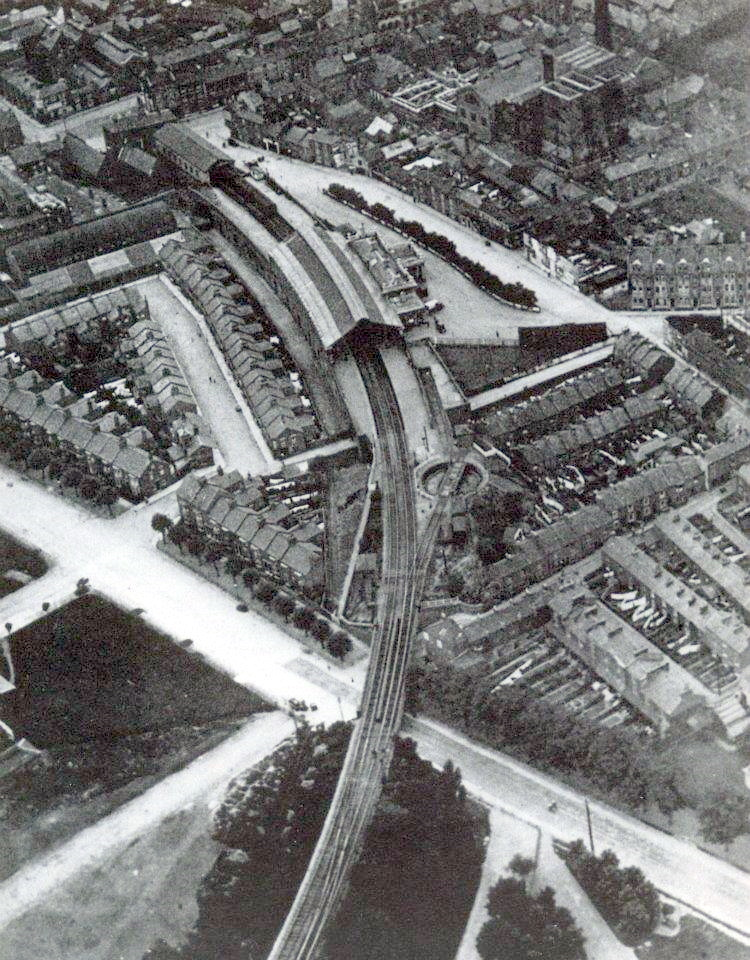

An aerial view of the station also showing the small shed at the terminus of the line behind buildings in Bridge Street.

Passing the booking hatch at St John’s Street Station onto platform 1, access to Platform 2 being across the tracks at the departure end of the platforms, both platforms were in use when two trains were waiting to depart, to Bedford and Wellingborough respectively but often there was only one train standing on platform 1 or a long period of no activity. The double track ran on through the Station to buffer stops in a two-coach length carriage shed above Bridge Street. This extension was laid in hope of a extending the line to Weedon and Daventry which of course never came about. Trains into St John’s were worked by Midland 0-4-4T tanks (12xx-13xx) classified by the LMS as IP (passenger).

Trips to Wellingborough

The same type of IP tank engines were deployed on the Wellingborough to Higham Ferrers branch with a stop at Rushden working from the up slow platform and leaving the Midland slows short of Sharnbrook. Northampton trains ran from a short bay at the southern end of Platform 2, the up main, and branched off onto a tight curve into Wellingborough London Road Station. Quite a number of services from Northampton ran through to Kettering or Leicester. Non-stop journey time was about an unbelievable 15 minutes somewhat more if stops were made at London Road. Castle Ashby and Earls Barton and Northampton Bridge Street although I don’t remember much activity other than taking a few parcels on or off at these stations.

Freight and Passenger services through Wellingborough

I bought many half-fare excursion tickets to Wellingborough which cost me no more than 6d for the half-day ticket or 9d for the full day, not much, but it still needed finding. The decision was always to bike or take the train. Usually the train was used in summer when by waiting for the last run back to Northampton at 8.40 p.m. it gave the opportunity to see the Bass beer train hauled by a Burton Crab, and the “Staybright Steel” container train containing ‘milk from contented cows’ hauled by a pair of Midland 4-4-0’s known by schoolboys as Simple’s to distinguish them apart from the 4-4-0 Compound. It was normal to double-head express trains with a pair of 4-4-0’s and coal trains with a pair of 0-6-0’s. In the early 1930’s the Midland ordered thirty-three 2-6-0-6-2 Garratts from Beyer Peacock, Trafford Park, Manchester which were equal to two 0-6-0’s when they had the chance to buy a more powerful design similar to those supplied by Peacock’s to railways all over the world.

All based at Toton the Garratts saved a footplate crew whose wages were minimal in those days. The Garratts were quickly withdrawn by British Rail when they took over in 1948.

King George V celebrated his Silver Jubilee as Monarch in 1935, the year LMS Chief Mechanical Engineer, William Stanier built 191 Jubilees at Crewe which were based all over the LMS system, making it difficult to see them all although I managed most other than half a dozen. (Scottish based, I believe). They were named after countries of the British Empire, explorers who founded these countries and the ships they sailed to bring the Empire about. The first to go was Windward Isles reduced to a heap of scrap in taking the full force of the Harrow disaster just after WW2.

Just before noon the Thames Forth (ex Edinburgh) and Thames Clyde (ex Glasgow) both via Carlisle and Settle to Leeds being scheduled to return from St Pancras mid-afternoon worked by a pair of Compounds was a highlight of early visits to Wellingborough. Later Jubilee’s took over. Perhaps a Derby Jubilee on the up journey and one from Kentish Town on the down train. A big day was when Derby allowed the Leeds engine to work through and once in a blue moon a Carlisle Jubilee was noted as far south as Wellingborough on its way to St Pancras. There was also the St Pancras-Sheffield trains running to compete with the Great Central, some running through to Leeds and Bradford and of course the afternoon St Pancras-Nottingham services, later to be known as the “Robin Hood” booked to stop at Wellingborough and when the limit of six coaches was relaxed to eight the sight of a Jubilee striving by Wellingborough sheds en route to Burton Latimer summit was something to be seen.

Wellingborough Roundhouses

The Roundhouse near to Mill Lane was for repairs as Wellingborough was an “A” shed, 15A, the second Roundhouse was the running shed beyond which was the coaling plant and water towers and numerous sidings for wagons of loco coal. The stabling roads between the two roundhouses were long enough to hold three locos. In my day they held some of the Garratts at weekends, in later BR times Wellingborough’s 2-10-0 Crosties were usually found here. Coal trains were resorted at Wellingborough before being sent on to London (Cricklewood).

Irchester

A Wellingborough Jinty did sorting at Irchester quarries (now the Country Park) and early afternoon a Garratt slipped off of 15A through the station to Irchester. Mid-afternoon it started its journey with 600 plus tons of iron-ore from Irchester to Wellingborough London Road via the curve to Midland Road station onto the Midland main crossing over to the slows at Finedon Road Bridge at some speed for the pull up to Burton Latimer and so the “Cargo Fleet” was on its way to the furnaces of that name at Redcar, Middlesbrough. This made sense as 3 tons of coal was needed to smelt one ton of ore. The Cargo Fleet left Wellingborough each afternoon and an empty Cargo Fleet returned the next morning. Easter Saturday 1943 when stationed at Catterick went with some rookie soldiers to Redcar by rail and clearly remember seeing the Cargo Fleet furnaces which I seem to recall showed signs of air raid damage which was not surprising considering its war-time importance. Army units were billeted in the sea front hotels, the beach was heavily barbed wired and there was no entertainment, a wasted journey other than an historical memory.

Sharnbrook

On a couple of occasions I cycled with some Wellingborough boys who lived in Westfield Road to Sharnbrook to watch the Garratts storm into the tunnel on the slow line and the Jubilees charge up the steep incline on the fast line. The Midland Railway built over land as they found it, hence many inclines on the main line, later on building to four tracks involved tunnels and cuttings that took the freight lines on a somewhat easier course.

That’s my Wellingborough story covering Cargo Fleet, Toton Garratts on long coal trains to London, Thames Forth, Thames Clyde and London-Nottingham Jubilee hauled express trains along with the Burton beer trains and visits to Wellingborough shed as well as many of the streets that were Wellingborough pre world-war two (i.e before the bombs dropped).

© Copyright : Graham Ward. All rights reserved.