A Sussex Son with a Fierce Spirit

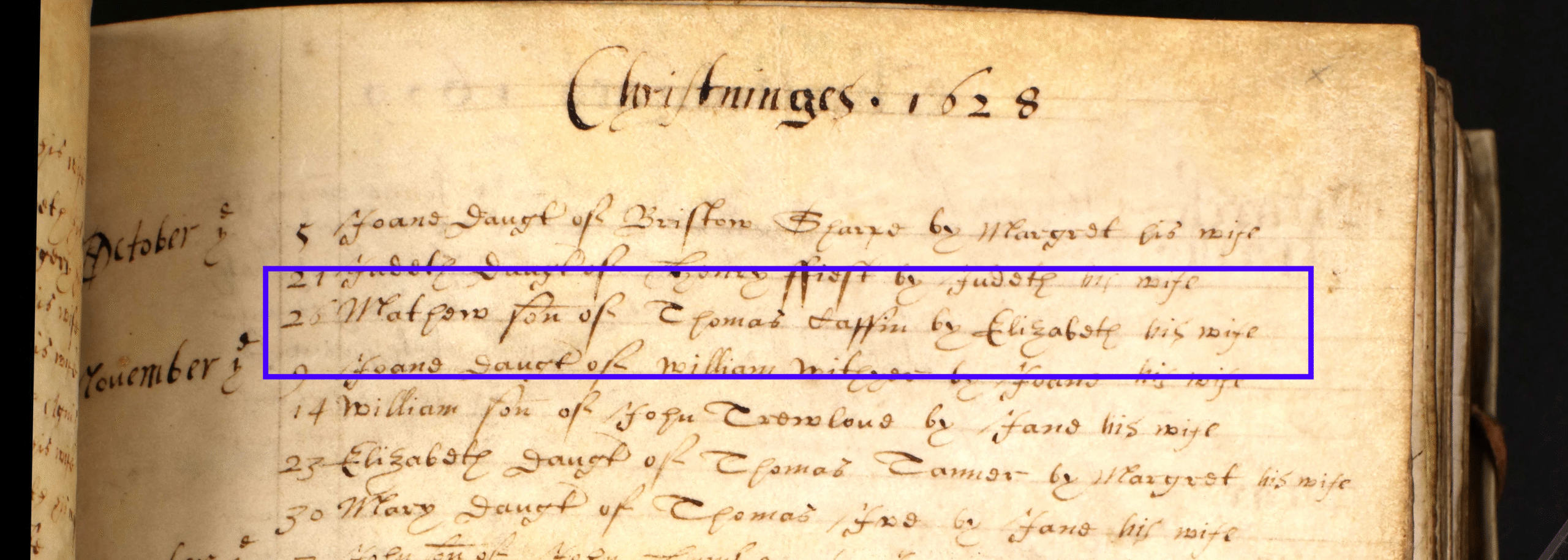

Matthew Caffyn (also spelt Caffin or Caffen) was born in Horsham, Sussex, and would go on to become one of the town’s most remarkable sons — a fiery preacher, theological rebel, and key figure in the early General Baptist movement. He was baptised at St Mary’s Church on 26 October 1628.

Humble Beginnings and a Generous Patron

He was the youngest of seven sons — his brothers John, Thomas, William, James, Francis and Richard were born between 1613 and 1623. Their parents likely married around 1611 or 1612.

Thomas Caffyn worked for the Onslow family, owners of Drungewick Manor near the Sussex–Surrey border. When Matthew was about seven, the head of the Onslow family offered to take him in as a companion for his son, Richard. This wasn’t adoption in the modern sense — more a practical arrangement that probably helped the Caffyns make ends meet. Thomas must have held a trusted position with the family, possibly as their bailiff.

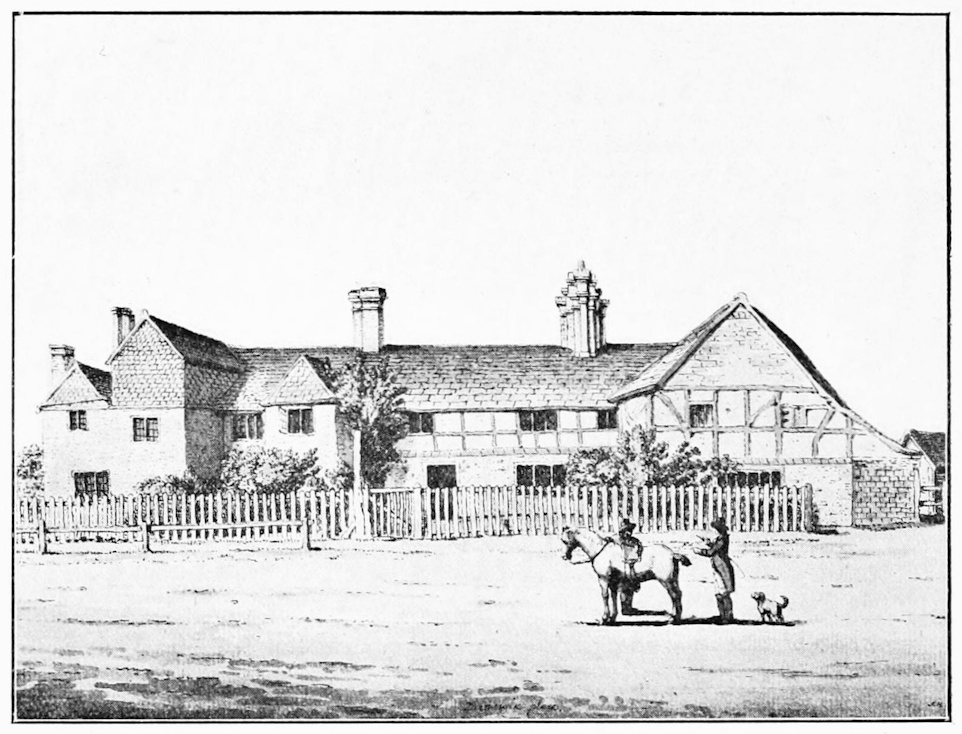

Matthew and Richard were sent off to grammar school in Kent, possibly in Canterbury. The boys grew up together, likely surrounded by the wood-panelled rooms and Horsham stone roofs of Drungewick Manor, which stayed in the Onslow family until at least 1664.

Oxford and the First Clash of Belief

At 15, in 1643, Matthew and Richard entered All Souls College, Oxford — a place meant to prepare students for a future in the Church. But Matthew didn’t follow the expected path. He openly challenged the doctrine of the Trinity and questioned infant baptism, which led to clashes with university authorities. Calm but unyielding, he refused to change his beliefs — and was expelled. He left Oxford with a clear conscience and a strong sense of purpose.

There’s no official university record of his attendance, but that’s no surprise — he never formally matriculated.

Farming and Preaching in Southwater

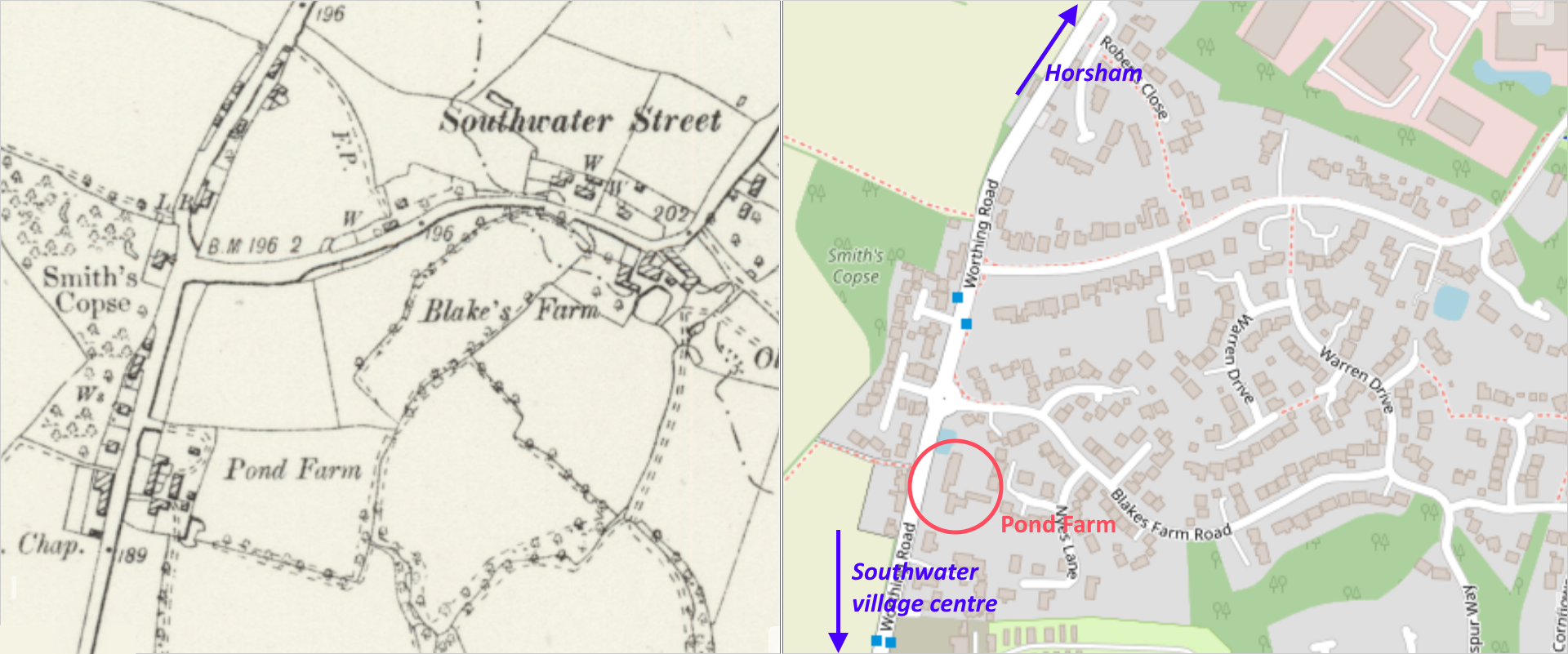

Matthew returned to Horsham in 1645, aged 17. His dreams of becoming an Anglican clergyman were over, but his ties to the Onslows remained. It may have been through them that he came to farm Pond Farm in Southwater, where he stayed for many years.

This was a time of religious upheaval. After the Reformation, all kinds of new sects sprang up — from Quakers and Ranters to Seekers and the oddly named Muggletonians (followers of a Puritan tailor who reportedly would only listen to preachers with short hair). Most faded away, but the Quakers and Baptists endured — and Matthew became a major figure in the debates between them.

By the early 1700s, there were an estimated 59,0003 baptists in England. They were divided into General Baptists (who believed Christ died for all) and Particular or Calvinistic Baptists (who believed he died only for the elect). The General Baptist movement began in London in 1611 and spread south to Kent and Sussex, and by the 1640s was established in the Midlands and Lincolnshire.

During the English Civil War, Baptist communities flourished — even within the army (though Oliver Cromwell himself wasn’t a Baptist). But things got tough again after the monarchy returned. The Conventicle Acts of 1664 and 1670 made it illegal for more than five people to worship together outside the Church of England. Informers were rewarded with a share of the fines.

It wasn’t until the Toleration Act of 1689 that non-Anglican worship became legal again. By 1727, Sussex had 45 Baptist meeting places — usually rooms in homes or rented spaces — and nearly all were General Baptist gatherings.

Most Sussex Baptists came from modest backgrounds — farmers, artisans, tradespeople. In Ifield parish, a Baptist meeting house was registered in 1713, though by 1724, there were just two Baptist families in the area. Horsham had more activity — with 350 attendees reported in 1717 — but only 18 Baptist families lived in the town.

The Making of a Messenger

Before Horsham’s Baptist chapel on Worthing Road was registered in 1719, meetings took place in private homes. When Matthew came back to the area, the local Baptist minister was Samuel Lover. Matthew soon became his assistant, and both men’s names appear on key Baptist confessions of faith from 16604 and 1690. According to historian Emily Kensett, Matthew took over from Lover as minister in 1648 — at just 20 years old5. By 25, he had been appointed a “messenger” to other churches and was one of the few Baptist leaders with any university training.

Matthew kept farming in Southwater, but his main work was preaching. He travelled widely across Sussex, Kent, Surrey and Hampshire, gaining a reputation as a powerful speaker and sharp debater. His boldness earned him the nickname “the Battle Axe of Sussex”.

He clashed publicly with the Quakers, who had a strong presence in the area. In 1655, two Quaker preachers from the north, Thomas Lawson and John Slee, argued with Matthew at a meeting in Ifield and then again at his home. The dispute was so fierce that it led to a flurry of published pamphlets on both sides.

He also took on George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, and debated with local vicars — including a Latin-language debate with the vicar of Henfield, which Matthew reportedly won.

Conflict Within the Fold

Not all of Matthew’s disputes were with outsiders. One long-running clash was with Richard Haines, a fellow Baptist, inventor and reformer6. Matthew disapproved of Haines’ connections with wealthy patrons and his pursuit of business ventures. In 1672, he excommunicated Haines, calling his activities scandalous. The matter dragged on for eight years until, in 1680, the Baptist Assembly ordered Matthew to lift the excommunication — a rare public setback for him.

In 1673, another Baptist minister, Thomas Monck, published a book7 attacking Matthew’s ideas. Though it didn’t name him, everyone knew it was aimed at Caffyn.

Matthew was at the heart of a bigger theological battle within the Baptist movement. Calvinist-leaning Baptists believed God had already chosen who would be saved. Arminians like Matthew believed in free will — that people could choose faith. In 1691, Joseph Wright, a fellow Baptist, accused Matthew of denying both the divinity and humanity of Christ and demanded his expulsion. The General Baptist Assembly rejected the claim. Wright tried again in 1693 — again, no action was taken8.

In 1700, churches in Buckinghamshire and Northamptonshire pushed for a proper trial. The Assembly agreed to address it at their Whitsun meeting — but Matthew’s supporters worked around it. Instead of a trial, they proposed a committee of eight (half supporters, half critics) to talk with Matthew and draft a statement. The statement avoided the tricky theological questions. The full Assembly voted to accept Matthew’s explanation and move on.

Not everyone was happy. Christopher Cooper of Ashford called Matthew’s beliefs a jumble of “Mahometanism, Arianism, Socinianism and Quakerism.” In 1701, some still pushed for a formal trial — but once again, the Assembly backed Caffyn. The dispute led to a short-lived split, but by 1704 — a year after Joseph Wright’s death — the breakaway group returned, and the dispute was settled.

Arrests, Imprisonment and a Lasting Legacy

Matthew’s boldness often landed him in trouble. He was fined and imprisoned five times under the Conventicle Acts. Once, in the awful conditions of Newgate Prison in London, he nearly died — only escaping thanks to the intervention of the Onslow family. He also served time in Maidstone and Horsham. During these hard years, his wife, Elizabeth, supported the family by spinning.

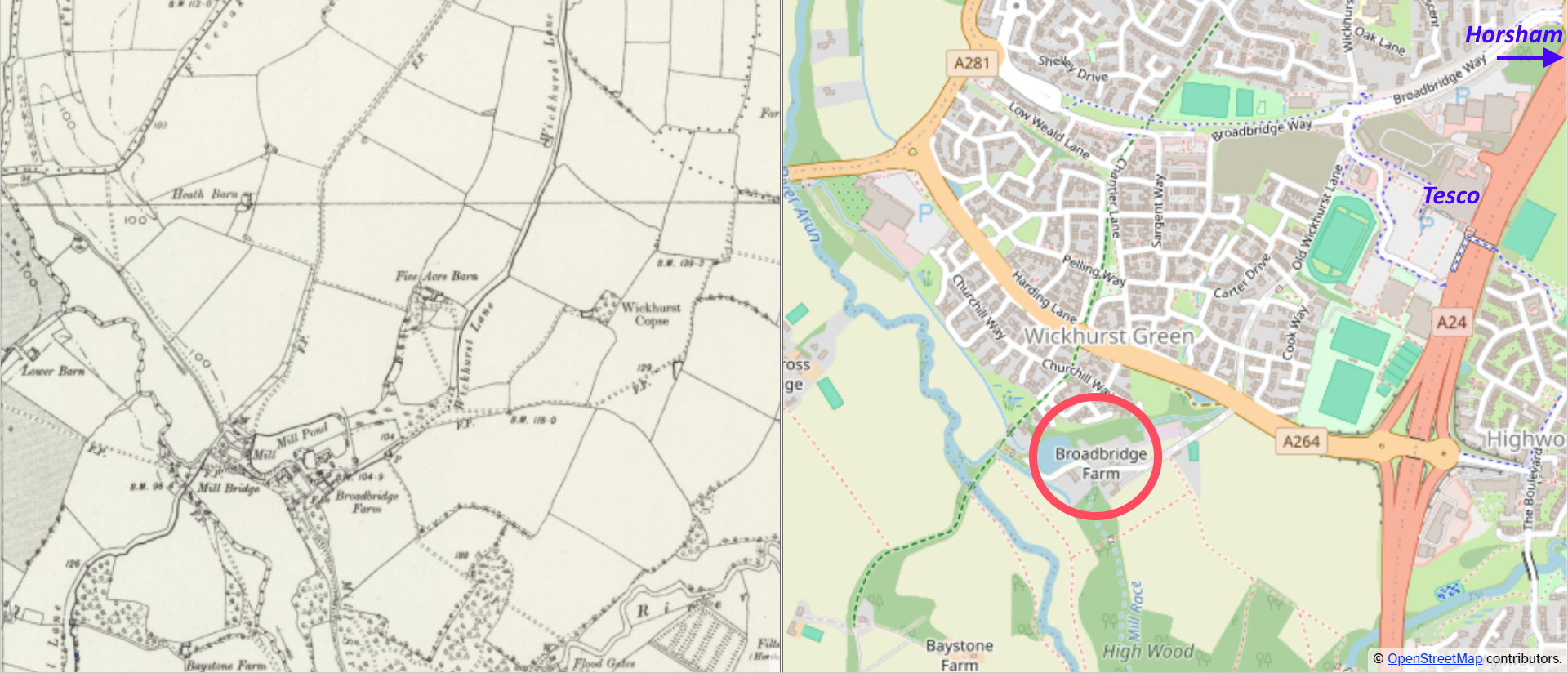

Later, Matthew moved to Broadbridge Heath, where he rented Broadbridge Farm and Mill — near where Tesco stands today. He lived there until he died in 1714.

The farm served as a meeting house, and the pond, like the one at Pond Farm, was used for baptisms.

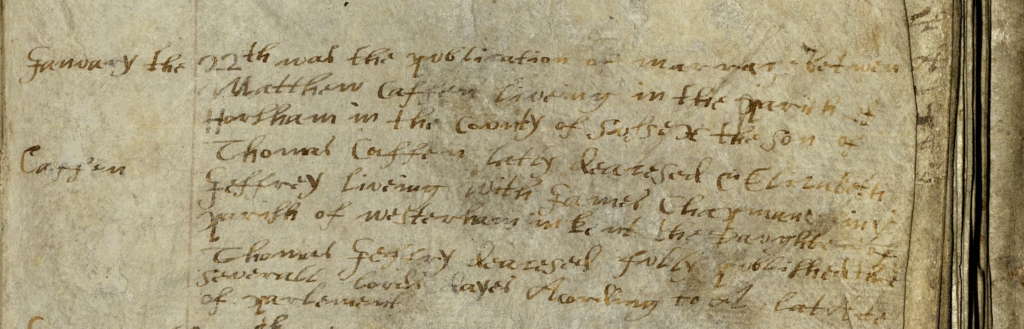

Matthew had married Elizabeth Jeffrey in 1653 in Westerham, Kent10. They had eight children — seven sons and a daughter. Their youngest son, also called Matthew, took over the Horsham ministry in 1710 and helped lead the new chapel in Worthing Road11.

Matthew Caffyn died in June 1714, aged 85. His wife had died in 1693. He was said to be buried under a yew tree in Itchingfield churchyard, though no headstone survives.

Today, a stained-glass window in Horsham’s Unitarian Church keeps his memory alive.

A Man of Conviction

What kind of man was Matthew Caffyn? Determined, bold, and principled. He could be difficult, but his convictions ran deep. He was a gifted speaker, a fierce debater, and a major force in shaping nonconformist faith in Sussex and beyond.

Digging deeper?

The debate about Matthew Caffyn’s place in history is not straightforward and continues today. For more on this, see Kegan A. Chandler, Unorthodox Christology in General Baptist History: The Legacy of Matthew Caffyn. Journal of European Baptist Studies 19:2 (2019)12 and Stephen R. Holmes, General Baptist ‘Primitivism’, the Radical Reformation, and Matthew Caffyn: A Response to Kegan A. Chandler. Journal of European Baptist Studies 21:1 (2021)13.

- Horsham, St Mary, West Sussex Record Office; Chichester, UK; Sussex Parish Registers; Reference: PAR 106/1/1/2

- British Library Add. MSS 5679 f.27

- ”From the information gathered in 1715-18 by the London Presbyterian minister John Evans, it is estimated that a total of almost 19,000 ‘hearers’ were found in about 120 General Baptist congregations, whereas 206 Particular Baptist churches had over 40,000” Brown, Raymond. The English Baptists of the 18th century. London, 1986.

- Lumpkin, William L., Baptist Confessions of Faith, Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1969, pp. 220-235

- Emily Kensett, Emily. History of The Free Christian Church, Horsham. 1921

- For details of the dispute between Haines and Caffyn, from Haines perspective, see: Haines, Charles Reginald, A complete memoir of Richard Haines (1633-1685), a forgotten Sussex worthy […] London, 1899

- Thomas Monck, A Cure for the Cankering Error of the New Eutychians. London, 1673

- General Assembly minutes for these years do not survive; thus we rely on Thomas Crosby’s account of the incident (Crosby, Thomas. English Baptists, vol. 3, pp. 280–85).

- Kent History & Library Centre, P389/1/A/1

- For a detailed discussion of marriage within the Baptist fellowship in Horsham, see: Caffyn, John. Sussex Believers: Baptist Marriage in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Churchman Publishing, 1988.

- Leonard J. Maguire, Records of the General Baptist Meeting House (Now Unitarian), Horsham, Sussex: Registers and Monumental Inscriptions (Transcribed, compiled & published privately by Leonard J. Maguire from the Unitarian & Free Christian Church, Worthing Road, Horsham, West Sussex, March, 1981.)

- Published: Dec 2, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25782/jebs.v19i2.223

- Published: May 20, 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25782/jebs.v21i1.701

© Copyright : Graham Ward. All rights reserved.