Jonathan Scott was a significant figure in the growth of Evangelical Christianity in the Midlands but came from a surprising background. A single-chapter biography of him has been published but this does not mention his early years in detail and his connection with Northampton is omitted.1

Royal Horse Guards Barracks

Shortly before the untimely death of the Northampton historian, Mike Ingram, I had been discussing with him the location and development of the Cavalry Barracks in the town. “The Blues” had been formed in 1650 by Sir Arthur Haselrigge (variously spelt as Haselrig, Hazelrig and Haselrigge) on the orders of Oliver Cromwell. In 1688 the Blues made Northampton their headquarters. This was not a surprising choice as Arthur Hasselrigge had earlier purchased the Northampton Castle site, and in 1680 the house in Marefair known as Haselrigg House (or Cromwell House)2.

It was not until 1750 that the regiment became known as the Royal Horse Guards. When the regiment returned to England in 1763 after the Seven Years’ War, they built the Army’s first purpose-built riding school at Northampton. The regiment remained in the town until their new Cavalry Barracks at Windsor had been completed and was ready for occupation in 1804.

The Riding School

Today The Riding is a well-known, albeit mainly service road for town centre properties in Abington Street and St Giles Street and the location of a small car park. In the mid-18th century, the Riding Ground was a significant feature and subsequently the location of the Royal Horse Guards Barracks. The date of the map indicates that a riding ground was established before the barracks.

The riding school building was part of a large establishment with stabling, coach houses, and a riding yard. The riding school was used for various purposes in addition to that from which it took its name. Sales were held there, and various performances took place in it. It had a pit gallery and upper gallery and could accommodate “nearly two thousand hearers”3 implying that the building must have been of large dimensions.

Jonathan Scott’s early life

Jonathan Scott was born at Shrewsbury, on November 15th, 1735. At the age of 17, he became a cornet in his Majesty’s 7th Regiment of Dragoons, following the profession of his father. He rose to be a Captain-Lieutenant, and in this capacity saw service in three campaigns including the battle of Minden in 1759.4

Scott’s conversion came about early in the 1760s whilst the regiment was quartered somewhere near Brighton (or Brighthelmstone as it was known until 1810). Scott had been out with a shooting party but was caught in a storm and took shelter with a farmer who had been looking after some of the regiment’s horses. Scott was persuaded to accompany the farmer to a nearby meeting where William Romaine, a prominent Evangelical preacher, was due to speak. Romaine made a great impression on Scott and he continued his relationship with Romaine both through meetings and correspondence for some time afterwards.

In Northampton

From about the middle of 1765, Scott’s company was quartered in Northampton. He knew the Rev John C. Ryland pastor of College Lane Baptist church, as he asked him to obtain apartments for him in the town. Ryland approached Mr Cooper, one of his deacons, who accommodated Scott. Whilst he stayed with Mr Cooper he took his turn in family worship; and it was here that he first spoke from a text of Scripture, which he continued to do during his stay in Northampton, for about a year. Here also he used to expound the Scriptures to those soldiers and their wives who were seriously inclined. During his stay in Northampton, he attended Ryland’s chapel regularly, but on the first Sunday in the month, he would go to Olney, to hear Rev John Newton and share in Holy Communion.5

Scott facilitated the use of the Riding House to accommodate Methodist meetings and was actively proselytising among the troopers of his regiment.6

John Newton and Jonathan Scott

Rev John Newton, the Evangelical clergyman of Olney, records in his diary:7

1766

‘Sunday, August 3rd. Captain Scott and Mr Barrett, two Christian officers from Northampton, visited us. Blessed be God, His grace appears in some instruments in every station of life. Our prayer meeting tonight greatly crowded.’

‘[August] 22nd. Captain Scott and Mr Barrett came, to avoid the races at Northampton. Thursday. Set out with my two friends to visit Mr Berridge [vicar of Everton, Beds.]; preached for him in the evening. I had a good number to hear me, and some from far.’

In a letter dated 20th March 1766, Scott wrote to a friend, possibly John Newton:

“I find that before I left the regiment, in order to go to Shrewsbury, I began to be a suspected person. Attending the ministry of such a notorious person as dear [William] Romaine, and associating with some Christian people, were sufficient to cause suspicions that I was turned this, and turned that. Upon my rejoining the regiment, I found it was no longer bare suspicion. Now they are convinced I am turned an arrant Methodist; and this their persuasion is a very lucky one for me; for now they begin to think my company not worth being over solicitous about, and I am sure you will readily believe that a very little of theirs is enough to satisfy me; or, more properly speaking, to dissatisfy me, so as to be tired of it, since their whole conversation consists in idle, vain nonsense, larded with horrid oaths and filthy obscenity; this is the more shocking to me, as I must sometimes be present at it, and have not in my power to remedy it.”

We know from John Newton’s letters that Scott first raised the issues concerning his commission in the army in the middle of 1766. Correspondence between the two continued intermittently between April 1767 and January 1773.8

The letters between John Newton and Captain Scott in 1767 includes the subject of the latter entering the Church. From this Mr Newton dissuaded him.

In August of that same year, Captain Scott writes again to his friend, telling him that his religious doings had awakened the notice and dislike of his commanding officer, who had in consequence determined to deprive him of his commission. And in the next letter to Newton, we have an interesting account of his interview with General Howard, the colonel of the regiment.

After a dinner, given by the colonel to the officers, he sent for me, and after many apologies told me he wanted to talk to me about my preaching. He had heard, he said, that I had perverted some of the soldiers to my way of thinking and that for his part he could not see that anyone had the right to draw weak and ignorant persons into such ways; that there was no knowing to what it might lead; adding that there were teachers in our own church to instruct them. He thought everyone ought to keep his religion to himself. I said it was quite true I had preached; that the Major (who was present) had heard me, and I hoped had not heard me advance anything inconsistent with the Scriptures. I also appealed to him whether I had in any way neglected my duty as an officer, or whether he found the soldiers whom the General said I had perverted had neglected theirs. He confessed that I was more diligent than formerly and that the men were good soldiers, only he thought them stupid. But why, the General asked, could not the men be taught in our own church? I said I had nothing to say against these teachers, but merely stated a fact when I said that they had gone to church for years without any appearance of religion amongst them, but when I had spoken to them, and got them together for religious worship, many of them were changed for the better. As to my having no right to do this, I was bound by the command of God to do all the good in my power, and I appealed to the General whether I ought not to have the same liberty to serve God without molestation, as others had to run into every excess, provided they did not break the laws of their country or the rules of the service. I said it was unfair to object to my drawing the soldiers from church, as I never met them at the times of public worship.

I concluded by saying I hoped the General would always find me an obedient and diligent officer as long as I remained in the regiment, but as for religious matters, I would never be controlled or guided by anyone in them further than they brought Bible authority. He candidly confessed he had no right over anyone’s conscience in such weighty matters.

In the course of my speaking to him, it came into my way to take notice of some oaths that were sworn during our being together after dinner, and some obscene talk, upon which I left the company. The General was one of the transgressors. I reminded him of it, and told him why I left. He confessed it was wrong; and so, after having on both sides hoped that there had been nothing said that had given offence, we parted very good friends, or seemingly so, he confessing he had nothing else to lay to my charge.9

The time came when it was no longer possible to continue both as a preacher and as a soldier on active service. He was ‘advised’ to leave the army and in March 1769 he sold his commission. Less than a year before this, on June I, 1768, he had married Elizabeth Clay of Wollerton, near Market Drayton, Shropshire, one who shared his aims and with whom he enjoyed over thirty years of happiness.10

John Newton’s relationship with John Ryland, Jr. son of the College Street Baptist minister John C. Ryland, continued after Scott had moved on from Northampton. John Ryland, Jr. recorded in his diary in 1768, [John Newton] preached at St. Peter’s, Northampton on August 11, 1768, where he heard him “with much pleasure”.11

The Methodists and John Wesley in Northampton

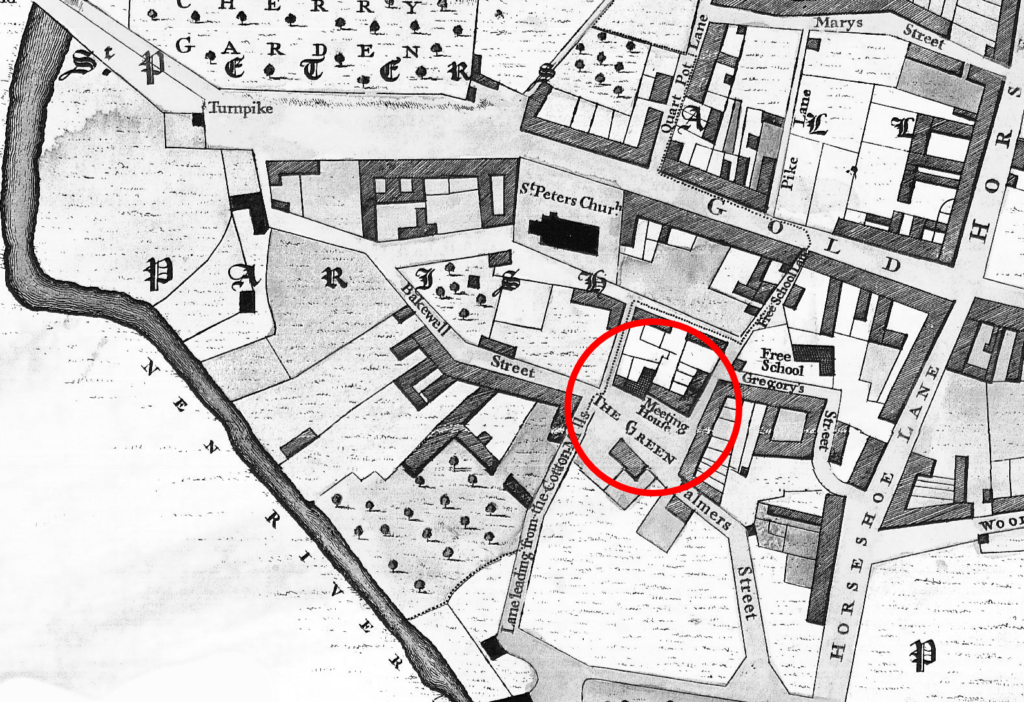

A small chapel on The Green in St Peter’s parish had previously been used by a group of Strict Baptists, but the building became vacant when their numbers dwindled and they merged with the larger College Lane Baptist meeting. Subsequently, the building was used regularly by the Wesleyan Methodists from about 1768 before they moved to a chapel in King Street in 1793.

In the second half of the 18th century, a significant faction of the Church of England focused around the leadership of John Wesley and George Whitefield. Their evangelical approach was particularly appealing to the middle and lower classes of society.

Scott obtained from Wesley the services of Richard Blackwell, a young itinerant preacher from the London Circuit. On August 24th he wrote to Wesley:

“The Lord has already begun to fulfil His promise here; He is working wonders amongst us; all denominations flock to hear the Word. The desire of the people to hear the Gospel from Mr Blackwell was so great they would not part with him till after Sunday. Your tender love to poor perishing souls will induce you to contrive that Mr Blackwell may return here soon.”

Wesley was not the man to neglect such an opening. On October 3rd Blackwell resumed his work in Northampton, where he was again well received. On Sunday, the 12th he exchanged with James Glassbrook, the Bedford preacher, who had nearly two thousand to hear him.12

On 15th October 1766, Captain Scott again wrote to Wesley:

“As long as our regiment stays at Northampton we can contrive to let them have our Riding House. The persons that came to me hope that you will continue to send them a preacher. Indeed, there seems to be a prospect of much good being done. I therefore trust you will take this affair into serious consideration, and send another preacher into the Bedford Circuit, who can take Northampton and two or three villages in, that I know would receive you. The Lord has opened you a door in Northampton.”

We can also hear John Wesley’s recollection of some of these events, particularly around his visit to Northampton.

Tuesday 27th November 1767

I rode to Weedon, where, the use of the church being refused, I accepted the offer of the Presbyterian meeting-house, and preached to a crowded audience. Wednesday, 28th, about two in the afternoon I preached at Towcester, where, though many could not get in, yet all were quiet. Hence we rode to Northampton, where, in the evening, (our own Room being far too small) I preached in the riding school to a large and deeply-serious congregation. After service, I was challenged by one that was my parishioner at Epworth, near forty years ago. I drank tea at her house the next afternoon with her daughter-in-law from London, very big with child, and greatly afraid that she should die in labour. When we went to prayers, I enlarged in prayer for her in particular. Within five minutes after we went away her pangs began, and soon after she was delivered of a fine boy.

Scott’s later career

From Scott’s initial religious experiences and association with the Methodists in Northampton and John Wesley in particular, it might be assumed that he would continue in this direction, but this was not the case. After Scott married in 1768, he settled in Wollerton, Shropshire and used it as his base for his preaching ‘campaigns’. He was not ordained by any denomination at this time but focused his attention on new causes and small groups of Christians often meeting in private houses. His relationship with John Wesley though deteriorated with the latter criticising Scott’s work during a sermon in Newcastle-under-Lyme in 1770. It was clear that Scott was aligned with the Calvinistic Evangelicals, like George Whitefield rather than the Arminian Methodists. However, Scott soon drew large crowds to his meetings with over a thousand hearing him at Stoke on Trent in 1773.

Following many visits to Lancaster, he was invited to pastor a church there which he declined fearing it would be too restrictive but agreed to be ordained as a ‘Presbyter or Teacher at large’ in 1776. His ‘circuit’ extended to a large area of Cheshire, Staffordshire, Lancashire and Derbyshire and his work is credited with the founding of about 22 churches many of which subsequently joined the Congregational Union. In the 1780s Scott struck up a relationship with the Evangelical benefactor Lady Glenorchy who provided funding for ministerial training and chapel building. Subsequently, on her husband’s death, she gave Scott a chapel and a house in Matlock, Derbyshire which Scott used as his base until he died in 1807.

- Shenton, Tim: Forgotten heroes of revival: great men of the 18th-century evangelical awakening, Leominster: Day One Publications, 2004

- The Cromwell reference derives from a local tradition that Oliver Cromwell spent the night at Hazelrigg House on his way to the Battle of Naseby in 1645. Unfortunately, this local reference isn’t supported by any documentary evidence.

- Quoted following the preaching of James Glassbrook a Methodist preacher from Bedford in 1768, from a series of articles by Rev G Beamish Saul (Wesleyan Methodist minister in Northampton 1903-1906), published in the Northampton Mercury, commencing 7th December 1906.

- Macfadyen, Dugald: The Apostolic Labours of Captain Jonathan Scott. Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society, Vol 3, pp 48-66

- Evangelical Magazine, 1808, p.194-5

- The Arminian Magazine, VI, 1783, 441–2.

- Extracts from: Bull, Josiah ‘John Newton of Olney and St. Mary Woolnoth. An autobiography and narrative, compiled chiefly from his Diary and other unpublished documents by the Rev. J. Bull’. Religious Tract Society, 1868

- The Works of the Rev. John Newton, T. Hamilton and J. Smith, 1821. pp117-147 ‘Eleven letters to J__ S__, Esq ‘

- Bull, Josiah ‘John Newton of Olney and St. Mary Woolnoth. An autobiography and narrative, compiled chiefly from his Diary and other unpublished documents by the Rev. J. Bull’. Religious Tract Society, 1868. pp160-162

- Robinson, W. Gordon ‘Jonathan Scott, 1735-1807’, Independent Press, London, 1962

- John Ryland, ‘Autograph Reminiscences’ (1807), Bristol Baptist College Archives 14883, p35

- From a series of articles by Rev G Beamish Saul (Wesleyan Methodist minister in Northampton 1903-1906), published in the Northampton Mercury, commencing 7th December 1906.

© Copyright : Graham Ward. All rights reserved.