A D-Day Veteran.

Lance Corporal no.14568781, 55 Construction Section, Royal Corps of Signals, part of 16 Air Formation Signals, attached to the Royal Air Force.

This photograph was taken in September 1944 by Edgar Barbaix in Ghent, Belgium

This photograph was taken at The Betjeman Arms, St Pancras Station, London

Arthur was born in Northampton in February 1925. He was called-up in the Autumn of 1942, initially into the Northumberland Fusiliers, then posted to the Royal Signals, attached to the RAF. After some 12 months signals training, in May of 1944 his unit was encamped on the banks of the river Orwell in Essex, pending embarkation for France. In 1994 Arthur wrote a memoir of his military service, including his D-Day involvement:

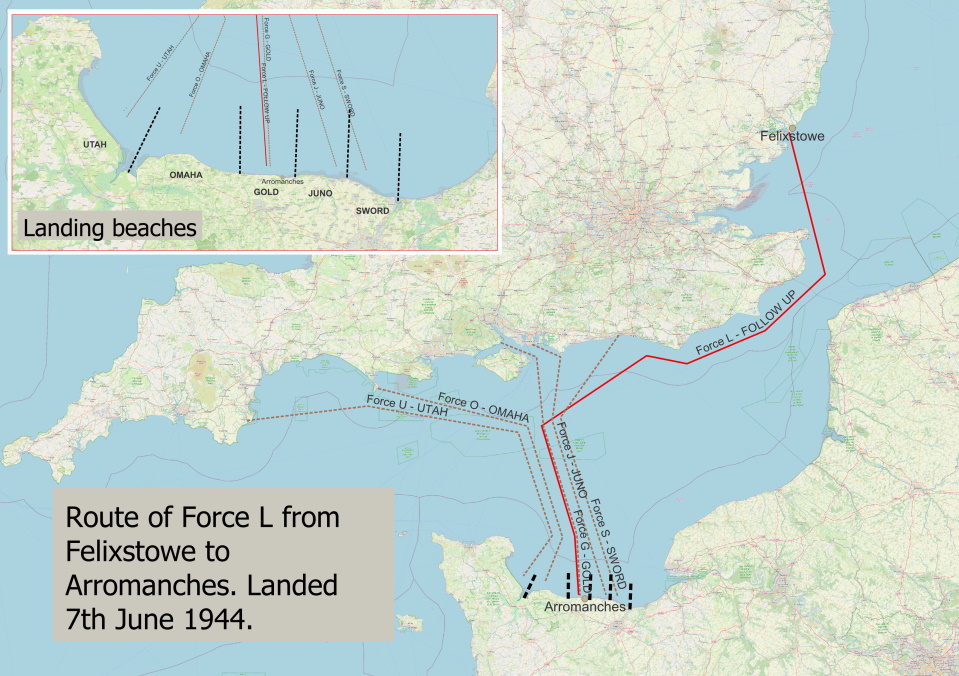

“On the afternoon of 31st May, 55 Construction Section left the field alongside the Orwell and motored to the nearby port of Felixstowe. Our Landing Craft Transport [LCT] stood at the jetty with her drawbridge down. Our lorries, trailers and trucks drove aboard forming two columns along the sunken open deck. They were covered by large camouflaged nets. The drawbridge was winched up. The LCT now sat low in the water with the extra weight of our thirteen vehicles and six very heavy trailers which were full of drums of cable, coils of wire, telegraph poles, picket posts, heavy hammers, picks, shovels, crow-bars and other tools, as well as all our kit. We were allowed to sleep on the deck as long as we were not too close to the side catwalks where the ship’s gunners would dash in an emergency. She had four Swedish ‘Bofors’ rapid-fire cannons on the port side, and about six machine gun positions. At the stern of the LCT a cable held the barrage balloon which flew about twice the height of a church steeple but could be winched much higher if need be. There was satisfaction that our ship could defend herself if attacked and no Stuka would dare to dive with the balloon cable in the way. The sailors were a friendly crowd.

That night we left England, the North Sea was calm and all night the chug, chug of the marine engine thumped away. At daybreak we were in the open sea and no one knew just where. On the evening of the second day at sea we came alongside the coast and Lance Corporal Bradford said we were off Deal in Kent as he recognised the castle. All that night the marine engine made a different thud and in morning we were surprised to see that we were in exactly the same position off Deal. The ship had been on sea anchors all night. All that day we stood still in that same position, the engine fighting against the anchor to avoid being swept onto the beach as, first the flow-tide, and then the ebb-tide rushed by. Sometime in the middle of that third night the ship got underway again and on the morning of June the 4th we were progressing slowly along the English Channel probably off the Sussex coast as land could be seen in the distance. The next day Bradford said we were off the Isle of Wight but the sailors either didn’t know, or they were not saying. One thing for sure, we were now crossing the English Channel as it became very choppy. There were hundreds and hundreds of ships many like ours and many more even smaller, the Landing Craft Personnel. The Captain said on the Tannoy that our mission had been held up for 24 hours due to bad weather and this was the reason for sitting-out a day on sea anchors.

D-DAY, 6th JUNE, 1944

On the morning of the 6th big guns could be heard in the distance. The guns got louder as our LCT moved closer to the coastline. They were the guns of the British battle fleet lined up along the French coast. The warships looked very small in the distance and their big guns poked out like snails horns. From time to time they flashed and explosions followed on the far off coastline about a minute later. Smoke was rising from the cliffs in the distance. Two German ME109’s flew low over the fleet and all guns turned on them. Our LCT rocked as all her guns were brought to bear on these targets. The planes turned and flew off. The RAF was not seen.

That afternoon our LCT ran aground about a quarter of a mile from the beach. The drawbridge was lowered and our vehicles entered the sea which came up the cab floor. The lorries strained with their heavy loads through the soft sand until they reached the strips of steel mesh matting which had been laid on the seabed as a makeshift road and very slowly we got ashore. The ‘beach marshals’ were shouting orders to do this, and do that, it was rather hectic, but certainly no panic. Our convoy was directed along some narrow lanes and Captain Davison turned into a field about a mile from the beach. After lining-up along the hedgerow with camouflage nets spread out, the night was spent sleeping under the vehicles.

The town near to where we landed was called Arromanches-sur-Mer. We were supposed to move towards the small harbour at Port-en-Bessin which was sheltered by high cliffs on which the big German guns were set in thick concrete emplacements. The battleships of the Royal Navy hit these emplacements but couldn’t knock out the guns. I believe that the Royal Marines landed on the coast some miles away and fought their way along the cliff tops to approach the German guns from the rear. Thereafter the German guns became silent.

The next day there were new orders to follow. Our convoy eventually turned into a field some five miles inland from the sea and for the first time it was explained to us what had happened and what we were to do. Several fields near Cruelly had been flattened and covered with steel mesh matting to form an aircraft landing strip. We were to lay two pairs of telephone wires inside a single cable towards the coast. For night after night the Royal Navy had been laying a marine communications cable on the sea bed starting from the English coast and getting ever closer to France.

Once the Allied landings had taken place the cable-laying was completed quickly and the end brought up onto the beach at Arromanches-sur-Mer into a vehicle called the “ocean terminal”. When completed our two pairs of wires were connected to the terminal and tested – contact had been made with TAF HQ at RAF Northolt back at Uxbridge. A problem developed as the telephone lines went dead – our own tanks had broken through the hedgerows and snapped the cable in many places. As fast as the cable was repaired, it got broke again. It was then decided that we should erect a line of small thin poles with the cable tied to the top of each pole. It was pointed out that this would take all our stores and the reply was that Lance Corporal Armstrong with Signalmen Murray and Wilcox were coming over on a supply ship with our back-up supplies. Twenty-four of us worked day and night to complete the link. Even before it was finished tanks and lorries had broken-down some of the poles. It became a full time job to keep the link open.

With no sleep for a week we were finally relieved. One day, Lance Corporal Armstrong arrived saying our supply ship had been sunk by the Luftwaffe and everything had been lost. He had been picked up from the sea by another ship. He was unable to say what had happened to Jock Murray, but he did see poor Wilcox go below the waves after being trapped under the camouflage nets.

We had lost our first comrade.”

Abridged from Arthur’s memoir. This text originally prepared for Northampton Museums & Art Gallery exhbition “D-Day 80”

© Copyright : Graham Ward. All rights reserved.