Pedigree Collapse and the Hidden Web of Shared Ancestry

If you start sketching a family tree, everything seems wonderfully neat at first.

- Two parents

- Four grandparents

- Eight great-grandparents

Each generation back, the number doubles. Simple.

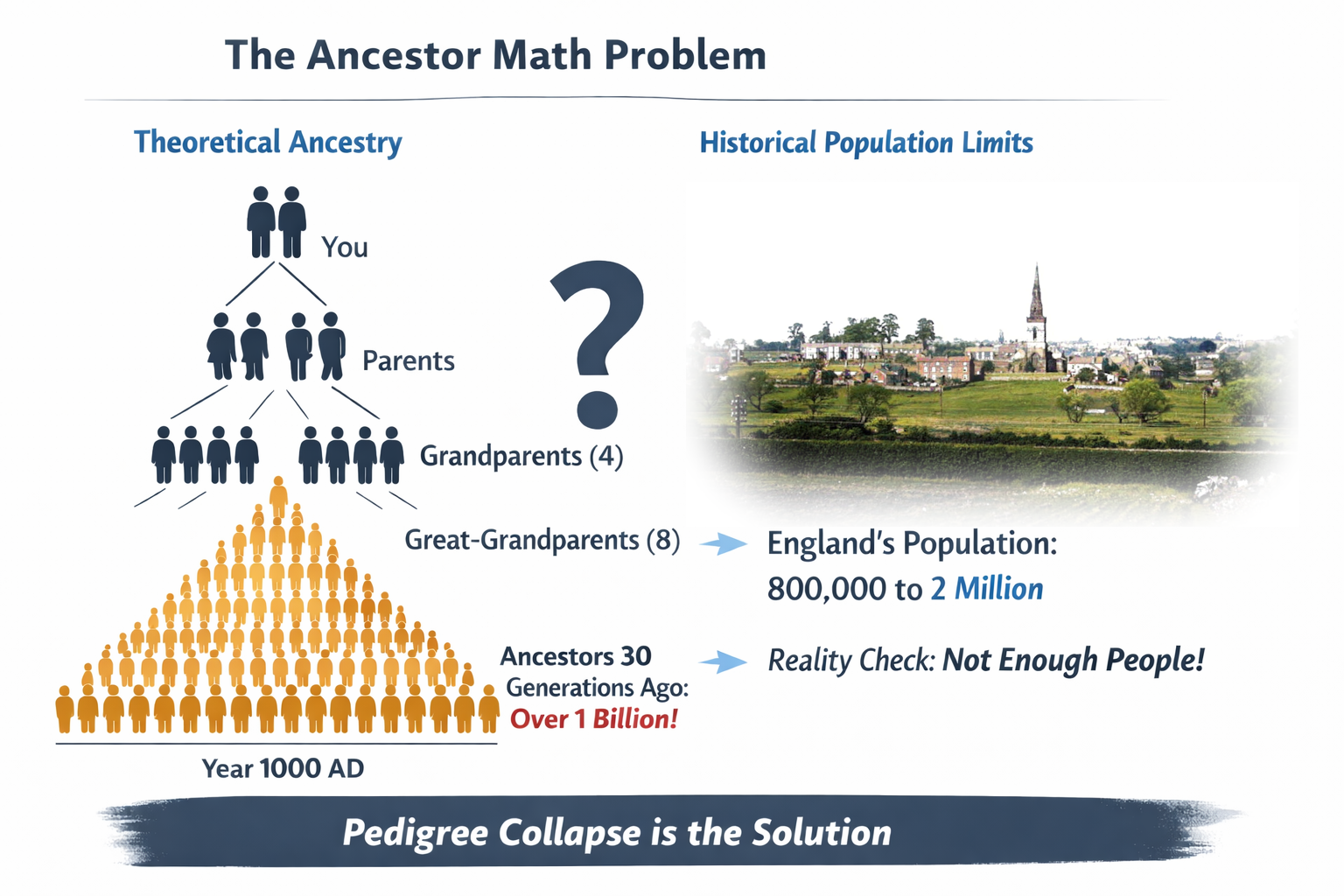

Keep that going for thirty generations—taking you back to around the year 1000—and you end up with a truly eye-watering figure: more than a billion ancestors. Which sounds impressive… until you remember a small historical detail. England, around the time of the Norman Conquest, probably had only one to two million people.

So, unless medieval England was quietly hiding several hundred million extra inhabitants, something in our tidy doubling maths clearly isn’t working. The missing piece of the puzzle is something called pedigree collapse.

The Illusion of Infinite Ancestors

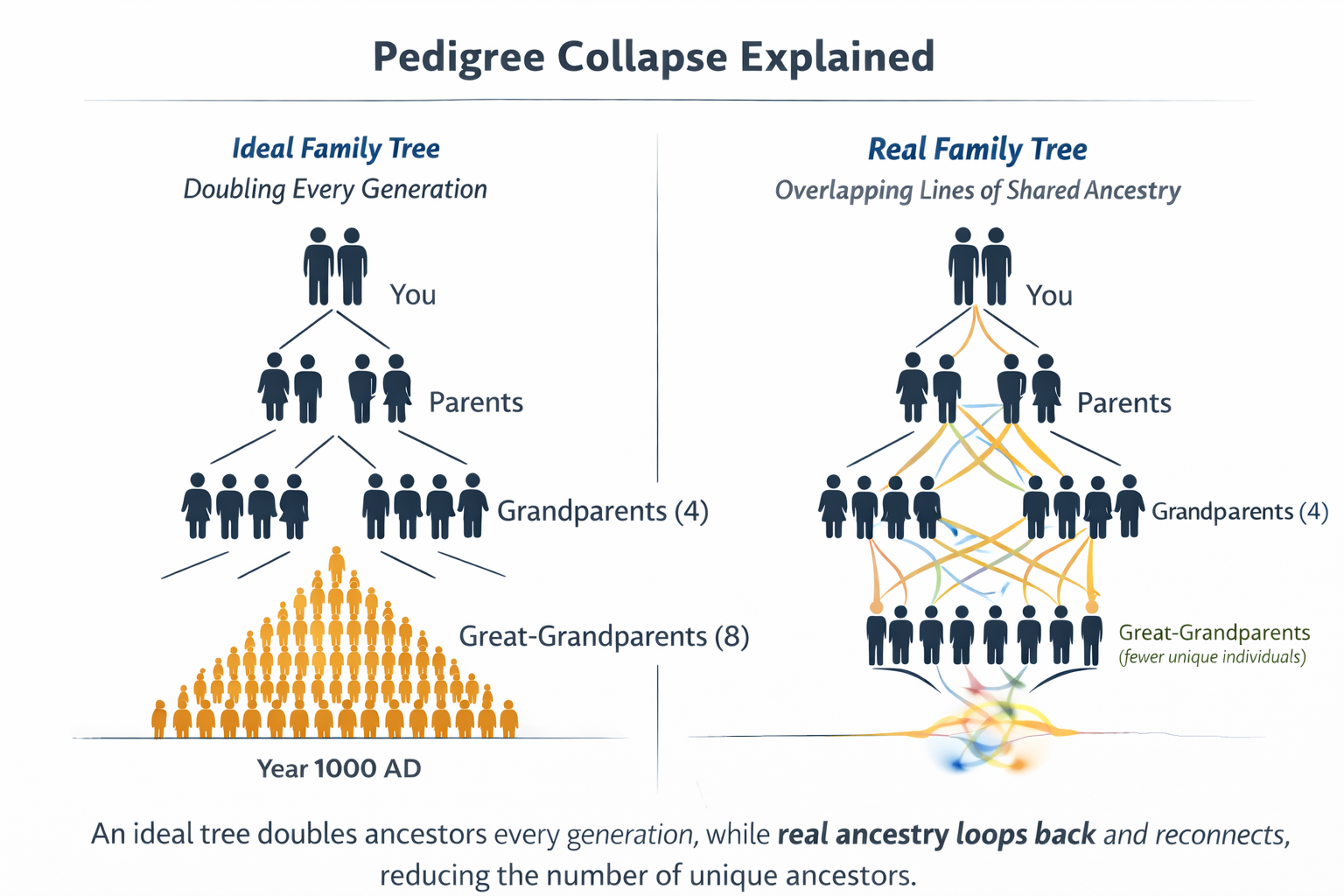

The doubling pattern assumes that every ancestor is a completely different person. In reality, human history just doesn’t work like that.

For most of the past:

- People rarely travelled far from where they were born.

- Communities were small and tightly knit.

- Marriage partners usually came from the same village, parish, or neighbouring area.

Over time, this means the same individuals start appearing multiple times in a person’s family tree. Your ancestry doesn’t expand endlessly outward. It loops back in on itself. That looping is pedigree collapse.

Pedigree Collapse and Marrying Within the Community

Pedigree collapse happens because relatives—often distant ones—marry each other. This pattern is known as endogamy, meaning marriage within a defined group.

Here’s a simple example:

If first cousins have a child, that child doesn’t have eight great-grandparents. They have six. Two ancestral “slots” are occupied by the same couple.

That may sound minor, but over many generations, the effect compounds.

Some historical demographers have argued that in pre-modern Europe, a large proportion of marriages were between people who were second cousins or closer1. Even where exact percentages are debated, the overall picture is clear: marrying within extended kin networks was common and unremarkable.

The result? Your family tree quietly collapses in on itself again and again.

Britain as One Very Large Extended Family

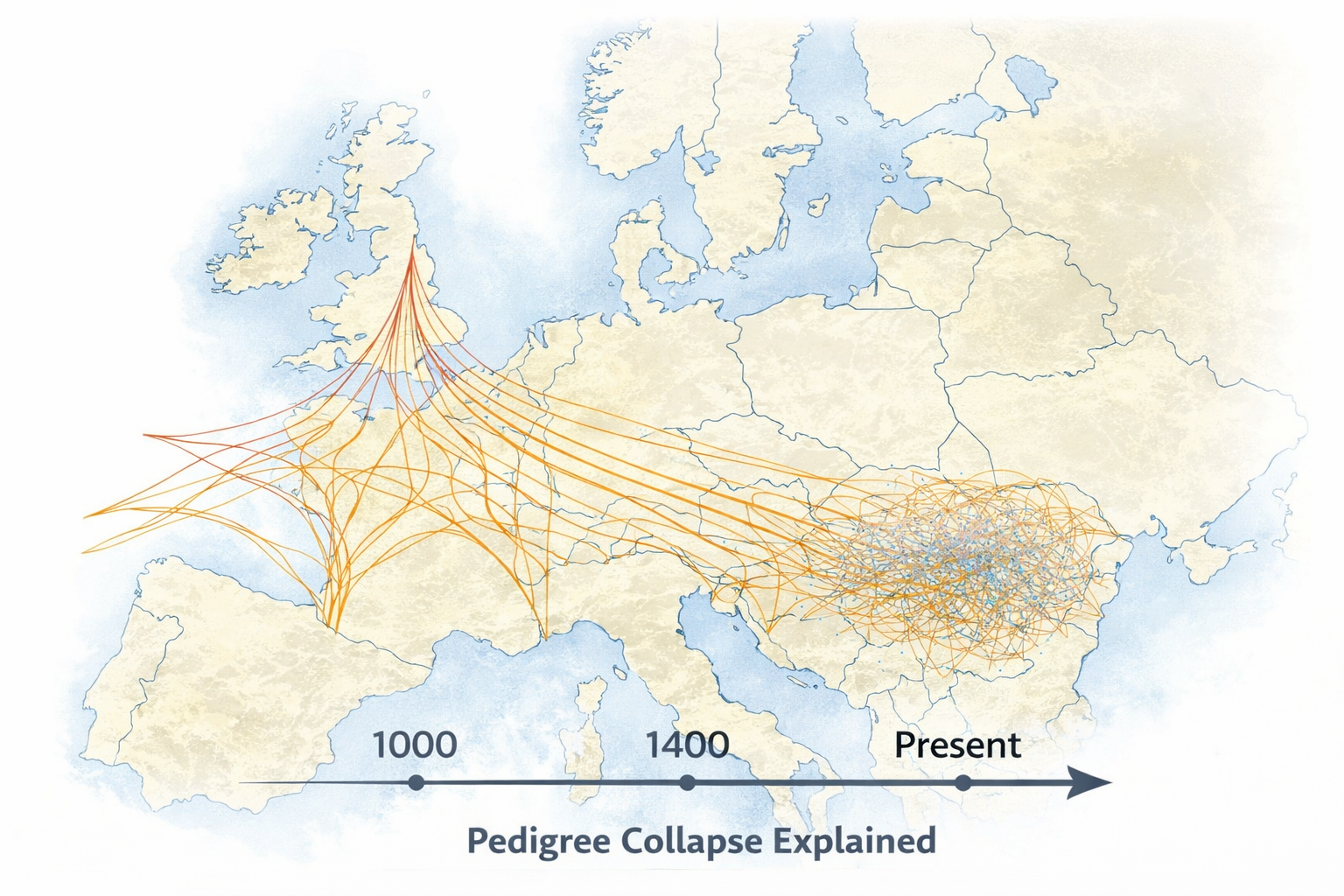

When researchers scale this idea up to entire populations, the results are startling. British genealogist Brian Pears concluded that virtually everyone alive in Britain around 1300 who left descendants is an ancestor of almost everyone living in Britain today2.

Demographer Kenneth Wachter estimated that about 86% of the population of England in 1066 are ancestors of all modern English people3. Statistician Joseph Chang, using mathematical models, showed that all Europeans share at least one common ancestor who lived around 1400 AD, and that by 1000 AD the majority of people who had children are ancestors of all living Europeans4.

In plain language:

If someone in medieval Europe managed to leave descendants at all, chances are extremely high that they are one of your ancestors. Not because they were special. Simply because enough generations have passed for family lines to blend together.

What Genetics Has to Say

DNA studies point in the same direction.

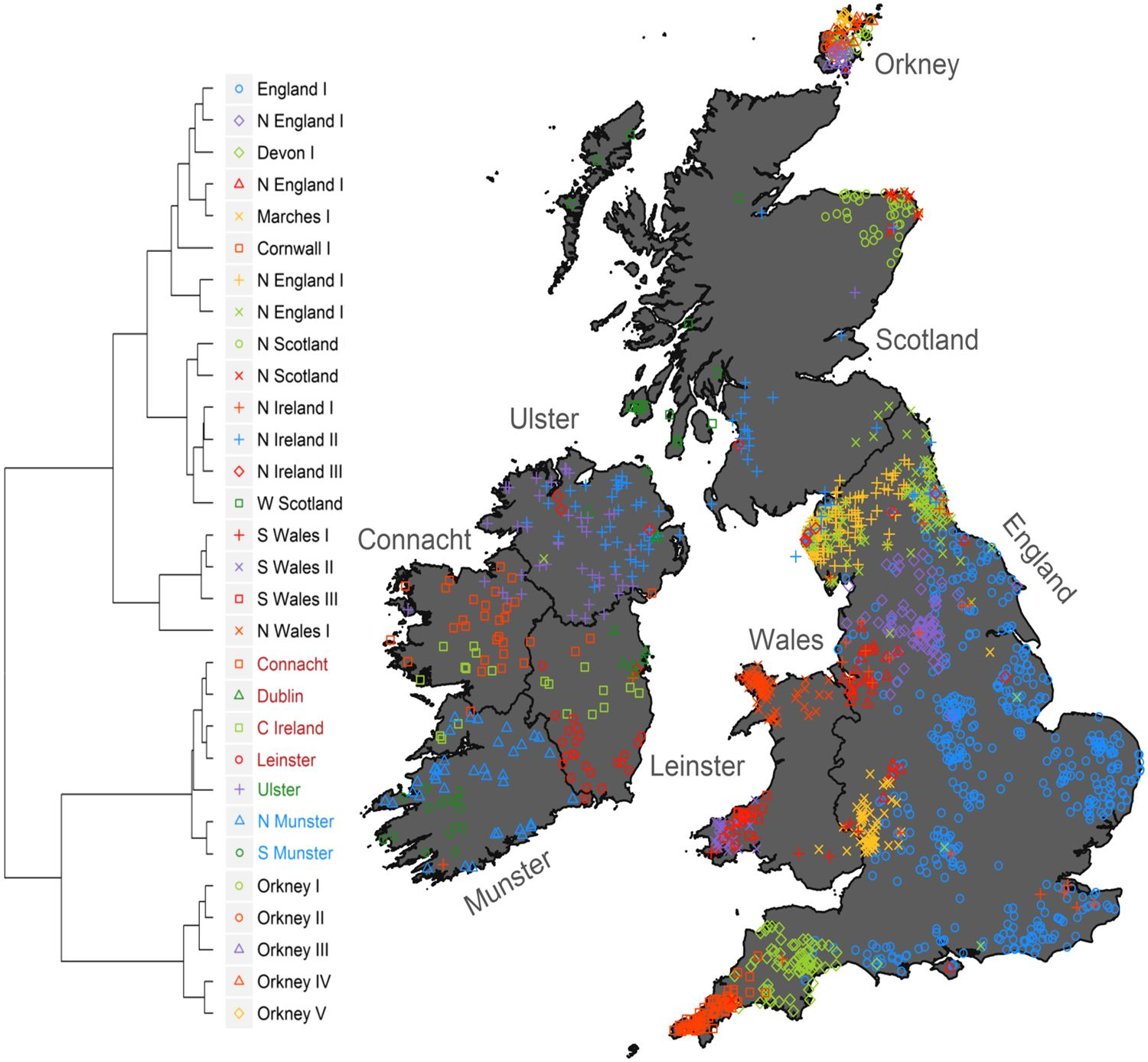

The People of the British Isles project5 analysed genetic data from thousands of people whose grandparents were born in the same rural areas. Researchers identified about 17 distinct genetic clusters across Britain, closely matching geography and historic kingdoms6.

A similar study, The Irish DNA Atlas, published in 2017, identified 30 distinct genetic clusters across the British Isles7.

Both studies suggest:

- Long-term population stability.

- People tended to marry locally for centuries.

- Regional ancestry overlaps heavily.

Interestingly, even dramatic historical events—like Viking or Norman conquests—often left smaller genetic footprints than we might expect. Cultural change was enormous; genetic replacement was much more limited. Continuity, rather than constant replacement, is the dominant story.

Clustering of individuals with Irish and British ancestry based solely on genetics8

You Are More Related Than You Think

Once pedigree collapse is taken seriously, a few comforting (and amusing) truths emerge:

- Two people with deep roots in the same region are almost certainly related multiple times over.

- Most people with British ancestry descend from medieval kings—but so do millions of others.

- Famous ancestors are not rare prizes; they are statistical side-effects.

Family trees aren’t trees – they’re webs.

A Web, Not a Tree

So yes, your theoretical number of ancestors explodes as you go back in time. But your real number of unique ancestors shrinks. Pedigree collapse bridges the gap between simple mathematics and historical reality. Not billions of strangers. But millions of shared forebears—ordinary people whose lives intertwined in ways that still shape us today.

- Bittles, A.H. (2001). Consanguinity and its relevance to clinical genetics. Clinical Genetics, 60(2), 89–98.

- “Our Ancestors, Conceptions, Misconceptions and a Paradox.” Brian Pears, 25 Dec. 2016, https://brianpearsblog.wordpress.com/our-ancestors-conceptions-misconceptions-and-a-paradox/.

- Wachter, K. W. (1978). Ancestors at the Norman Conquest. In: Statistical Studies of Historical Social Structure, pp. 153–161. Edited by K. W. Wachter, E. A. Hammel & P. Laslett. Academic Press, New York

- Chang, J.T. (1999). Recent Common Ancestors of All Present-Day Individuals. Advances in Applied Probability, 31(4), 1002–1026.

- Population Genetics. https://peopleofthebritishisles.web.ox.ac.uk/population-genetics. Accessed 31 Jan. 2026.

- Leslie, Stephen et al. “The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population.” Nature vol. 519,7543 (2015): 309-314. doi:10.1038/nature14230 Online version: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4632200

- Gilbert, Edmund, et al. “The Irish DNA Atlas: Revealing Fine-Scale Population Structure and History within Ireland.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, 2017, p. 17199, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17124-4. Accessed 31 Jan. 2026.

- Edmund Gilbert, Seamus O’Reilly, Michael Merrigan, Darren McGettigan, Anne M. Molloy, Lawrence C. Brody, Walter Bodmer, Katarzyna Hutnik, Sean Ennis, Daniel J. Lawson, James F. Wilson & Gianpiero L. Cavalleri, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

© Copyright : Graham Ward. All rights reserved.