Fragments of the past: every record tells a story, but none tells the whole story

Family historians (genealogists) are sometimes regarded with suspicion by “proper” academic historians. The reason is not difficult to understand. Family historians usually begin their research with a personal stake: they are trying to reconstruct their own past. From the outset, therefore, they are not merely collecting data but shaping a narrative—often unconsciously—about who their ancestors were and what their lives meant.

Yet this tension between evidence and interpretation is not unique to genealogy. All historians, whether writing about monarchs or mill workers, face the same fundamental problem: the past only survives in fragments, and those fragments were created by human beings. What differs in family history is simply how close to home these uncertainties strike.

To research responsibly, we must learn to doubt—not cynically, but critically—our own version of history.

Human Error: The Weakest Link

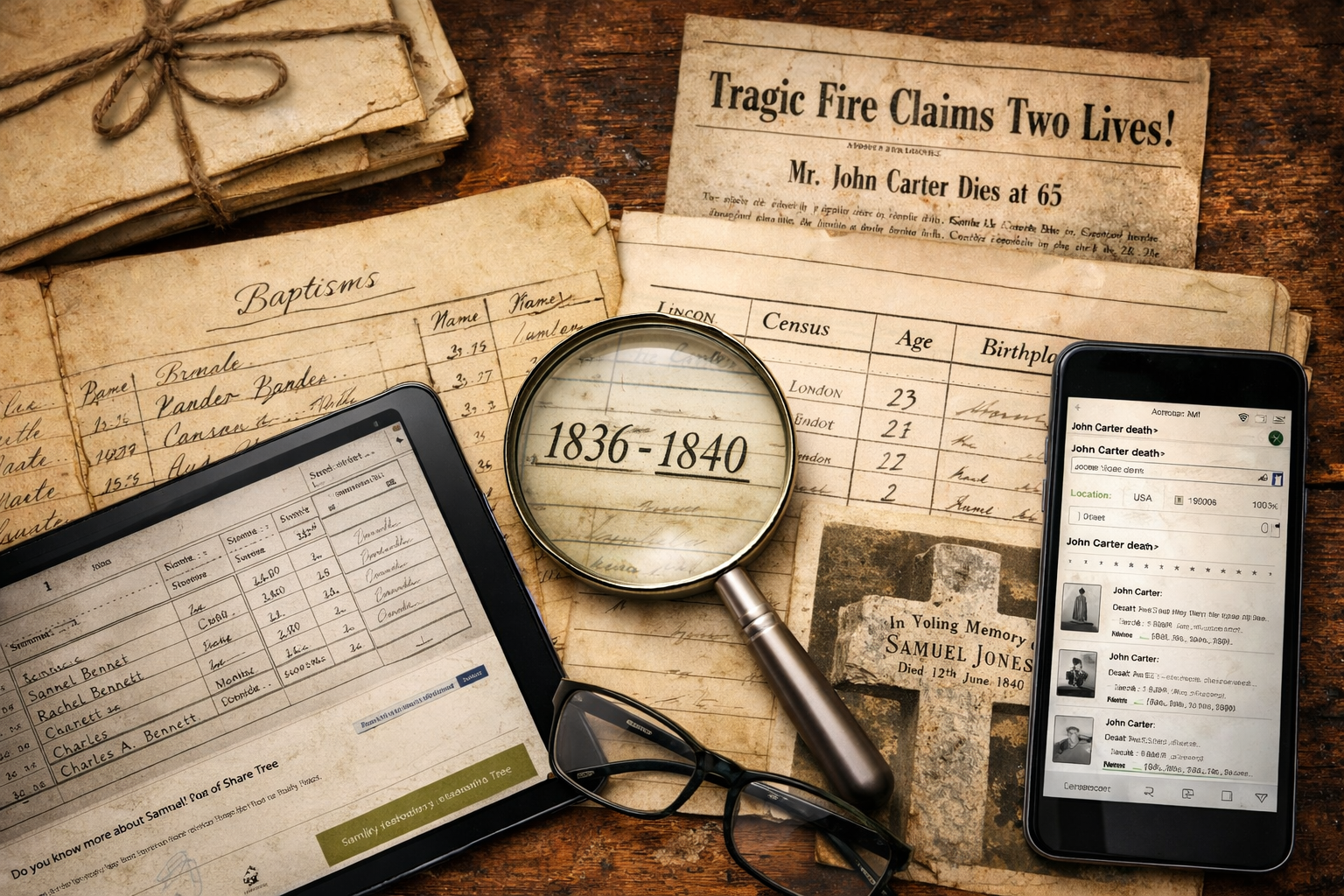

Almost every historical record rests upon a chain of human action. Someone observed an event, someone reported it, someone recorded it, and often someone else later transcribed or indexed it. At any point in this chain, error can enter.

Much genealogical information depends on the knowledge of an informant who may not have known the full truth. A widow registering a death may never have known her husband’s exact birthplace. A neighbour supplying census information might guess a person’s age. A grandchild recalling a grandparent’s childhood may unknowingly compress or distort decades of memory.

Even when informants are accurate, mistakes still occur. Clerks mishear names. Enumerators write hastily. Modern transcribers misread faded handwriting. A single miscopied letter can create a new surname that never previously existed.

Monumental inscriptions appear authoritative, carved in stone and seemingly permanent, but they too are products of memory. A gravestone may record a precise birth date that contradicts baptism registers and census returns. In many cases, the stone was erected long after death by descendants relying on family tradition rather than documentation. The stone does not lie, but neither does it necessarily tell the truth.

Recognising the fallibility of records does not mean rejecting them. It means treating each one as a piece of evidence rather than a final answer.

The Nature of Sources

Not all sources carry equal weight. Some records were created close to the time of an event, while others were compiled much later. Parish baptism registers, burial entries, and contemporary letters usually preserve earlier memories than local history books or modern online family trees.

Secondary and compiled sources have enormous value, but they are interpretations of earlier material, not the material itself. A printed genealogy may look authoritative, yet its conclusions may rest on assumptions, guesswork, or earlier unverified research.

Online databases and shared family trees present a particular danger. An incorrect parent-child link, once uploaded, can be copied hundreds of times. Repetition creates the illusion of certainty. The same error appearing in multiple places may trace back to a single flawed assumption.

The responsible researcher therefore learns to ask not “Where did I find this?” but “What is this ultimately based on?”

Census Records: A Case Study in Uncertainty

Few sources are used more heavily by family historians than census returns, and few are more easily misunderstood.

A census is not a full biography. It is a snapshot of what one person in a household told an enumerator on one particular day. Ages may be approximate. Birthplaces may be simplified. Relationships may be misunderstood or deliberately disguised.

A woman who appears aged thirty in one census, thirty-eight in the next, and forty-five in the next may not be deliberately misleading anyone. She may simply be uncertain herself, or unconcerned with precision.

Rather than asking which census is “correct,” a better question is what range of possibilities the combined evidence suggests. The truth often lies somewhere between the numbers.

Social Pressure and Self-Presentation

Historical records do not merely describe reality; they reflect how people wished to be seen.

Throughout history, respectability has mattered. Unmarried mothers might describe themselves as widows. Couples might exaggerate how long they had been married. Young brides might add a few years to their age. Men might upgrade their occupation from labourer to builder, or from clerk to manager.

Such alterations were usually not grand deceptions. They were small acts of self-protection in a society that judged harshly. But they shape the records we now rely upon.

Understanding this context helps us read sources with empathy as well as scepticism.

Third-Party Narratives: Newspapers and Local Histories

Digitised newspapers have revolutionised family history research. They offer colour, detail, and voices that rarely appear elsewhere. But newspapers are secondary sources, and often unreferenced ones.

Journalists wrote to attract readers. Sensation sold. Minor disputes could become dramatic confrontations. Tragic accidents might acquire melodramatic flourishes. Even straightforward reports may contain errors introduced in the rush to print.

Family notices—births, marriages, deaths—are usually reliable but still supplied by relatives who may be mistaken.

Newspapers should be treated as valuable clues, not unquestionable proof.

Memory Is Not Evidence

Family stories often form the emotional core of genealogical research. They connect us to the past in ways that documents cannot. Yet memory is fluid.

Stories are shortened, simplified, and reshaped with each retelling. The “army officer” becomes, on closer inspection, a private. The “wealthy ancestor” turns out to have struggled throughout life.

These discoveries do not diminish our ancestors. They reveal them as ordinary people navigating difficult circumstances.

Confirmation Bias: The Hidden Trap

One of the greatest dangers in family history is not missing evidence but selective attention.

Once we form a theory—about a prestigious ancestor, a dramatic migration, or a romantic scandal—we naturally notice evidence that supports it and overlook evidence that contradicts it.

Good research actively looks for disconfirming evidence. It welcomes challenges. It treats surprise as a signal to investigate further rather than something to explain away.

What Responsible Genealogy Looks Like

Responsible family history is cautious, transparent, and provisional. It weighs multiple independent sources. It records uncertainty. It uses language that reflects probability rather than certainty.

Most importantly, it remains open to revision.

Genealogy is not about proving a story. It is about testing one.

Conclusion

Doubting your version of history does not mean abandoning it. It means strengthening it.

Family history is not a fixed portrait. It is a continually evolving sketch, refined as new evidence appears and old assumptions are questioned.

In this sense, genealogists and academic historians are engaged in the same endeavour. Both attempt to reconstruct human lives from incomplete and imperfect traces.

The difference is simply that genealogists feel the weight of that uncertainty more personally.

And perhaps that is not a weakness, but a strength.

© Copyright : Graham Ward. All rights reserved.